If you found anything of interest in my previous autobiographical post, A Taste of War.... here is a continuation. It is not in any way about jazz or blues (although, perhaps, tangentially, the latter), but all this stuff from my memory bank somehow comes together—at least for me—and is readily skipped.

When the Godafoss sailed up the East River and docked, I saw none of the marble structures, fancy people and glitter that had summed up New York in my little mind, but I did see tall buildings and a grimy waterfront. I was disappointed yet excited, because our arrival was attracting a lot of attention. A hoard of gum-chewing, loudmouthed newspaper reporters and photographers stormed aboard and flashbulbs seemed to be going off everywhere. You have seen this in old movies—Hollywood really got it right.

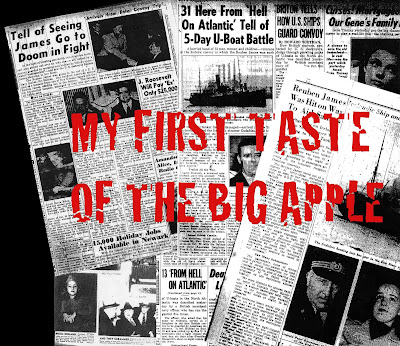

As I said in the previous post on this subject, it was not until many years later that I realize what had sparked the interest in our little tub: we were, as one paper put it, survivors of a “Hell on Atlantic,” a 5-day cat and mouse game that had killed 100 sailors and cost the U.S. Navy its first casualty of the European war. Of course, Pearl Harbor changed things exactly a month later.

There were two press people aboard the Godafoss on this trip, one a newsreel cameraman, Neil Sullivan, the other a reporter, Larry Kennedy. I recall one of them being pulled down and given the old “Women and children first” admonition as he attempted to scramble into a lifeboat. Our situation was not to be taken lightly, but I think the grown-ups were more aware of that than Kanda and I.

Our first New York residence was an apartment in the Raleigh, a fairly luxurious hotel building on West 72nd, just down the street from the Dakota. During the month that we stayed there, Adda, our maid, was taking Kanda and me for a walk in the park when an effusive lady stopped us to say that she had just seen us in a newsreel. We headed straight for the newsreel theater at 72nd and Broadway and—sure enough—there we were, filmed on deck, peered through one of the ship's lifesavers. I wonder if that footage still exists?

We had not yet left the Raleigh when the news of Pearl Harbor hit the streets. Remember, this was an era of shouting news boys, so it really did hit the streets, as an Extra! Extra!. At first, I didn't quite catch the significance of that news, but I soon became as wrapped up in WWII happenings as any American kid. By Christmas of 1941, we had moved to a fairly large rented house at 115-27 Union Turnpike in Forest Hills, not far from Queens Boulevard. The house was still there last year when I took a camera along for my first visit to the neighborhood in 65 years, so was our second house, at 66 Beechknoll Road.

Both looked exactly as I remembered them. We didn't stay long at the first house, perhaps because the neighbors complained. Stella, I soon learned, was an alcoholic and there were constant loud arguments. It didn't take long before our maid, Adda, called it quits and ran off with a Finn named Bruno. I never saw her again, but she later spearheaded an effort to "rescue" me—more about that in a future post.

Both looked exactly as I remembered them. We didn't stay long at the first house, perhaps because the neighbors complained. Stella, I soon learned, was an alcoholic and there were constant loud arguments. It didn't take long before our maid, Adda, called it quits and ran off with a Finn named Bruno. I never saw her again, but she later spearheaded an effort to "rescue" me—more about that in a future post.Here Adda poses with me and Stella in front of the house. The picture was taken in 1942—same eaves over the front entrance.

Kanda and I pose in the same spot with my father in June of 1944.

When I was enrolled in school, at P.S. 101, my English vocabulary couldn't fill a file card, but it was growing every day. Of course I could not attend the class my age called for, so they assigned me to a class where I towered above my classmates. Kids have a knack for absorbing in a short time any language that surrounds them, but Lisa Clausen, a little English-speaking Danish girl seated at an adjoining desk, gave me an added advantage.

As my English improved, they moved me to a more age-appropriate class, but it didn't really make much difference, because the standard of education at P.S. 101 was deplorably low. From January 1941 until the summer of '44, all I learned was how to make a papier maché puppet head, weave patches for a wool blanket, recite from memory Joyce Kilmer's Trees, and sing patriotic songs. Yes, I could hold a simple conversation in English by the time I left, but there were no lessons in grammar, so I knew no rules and—as you may have noticed—I still don't, neither in English nor Danish or Icelandic.

At P.S. 101, we spent much time marching around on the auditorium stage in our military uniforms from Woolworth's on Austin Street, proudly waving the stars and stripes, and singing about the caissons rolling along from the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli—you get the picture. I caught the spirit, started a little Victory garden, bought War Bonds with what little pocket money I had, wore a button that showed a hanged Hitler (when one pulled a string), collected photos of war planes, and drew my own patriotic comics. When I look at my crude home-made comic books, I realize how quickly I learned rudimentary English and how intellectually handicapped I was. This comic book (I don't know how it survived all these years) also reminds me that I desperately wanted to distance myself from my father, which is why I credited myself as "Gunnar Broberg." Gunnar is my middle name and I used to be known by it, but Broberg is my Danish family name. Silly, in retrospect, but my stay in the U.S. had become somewhat of a nightmare.

The Toigos, Adolph and Lucy, lived in the house that adjoined 66 Beechknoll Road. He worked for one of the big advertising agencies (his boss, Milton Biow, brought us "Johnny," the Philip Morris bellhop, and radio's $64 Question). Their two sons, Oliver and Alfred, were around my age, so we became very good friends. Adolph had become the head of Lennen and Newell, one of the top ad agencies by 1954, when my wife and I came to New York on tourist visas. I looked the Toigos up and found them living in the Waldorf Towers. They also owned a farm in Connecticut and had held onto the house in Forest Hills. Lucy, whom I remembered as a floor-scrubbing, apple-candying housewife, now looked as if she had just stepped out of a society page photo, but she was still the warm and wonderful next door neighbor who so often had taken me in for the night. Let me explain that in a sequel post.

No comments:

Post a Comment